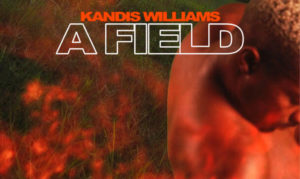

Installation shot, "Kandis Williams: A Field." Photo by David Hale.

Installation shot, "Kandis Williams: A Field." Photo by David Hale.

Installation shot, "Kandis Williams: A Field." Photo by David Hale.

Installation shot, "Kandis Williams: A Field." Photo by David Hale.

Installation shot, "Kandis Williams: A Field." Photo by David Hale.

Installation shot, "Kandis Williams: A Field." Photo by David Hale.

Installation shot, "Kandis Williams: A Field." Photo by David Hale.

Kandis Williams: A Field

Nov 6, 2020 – Sep 12, 2021

OVERVIEW

A Field is a new, site-responsive commission by Kandis Williams (b. 1985, Baltimore, MD). Williams addresses the regimes of control associated with labor, including at prison farms in Virginia. A Field takes place within a greenhouse, surrounding the viewer with plant sculptures. These works feature photographic collages affixed to the wire forms of monsteras, palms, banana trees, and vines, appearing variously in pots on the floor or on greenhouse benches, as well as along the gallery walls. For Williams, collage is able to choreograph and index both thought and movement. The medium allows Williams to merge contemporary and historical referents, exposing the entangled relationships between humans and non-humans subjected to destructive world-building.

These collages, which appear on the plant leaves and as backdrops throughout the gallery, depict laboring bodies in action. They include archival photographs of chain gangs on Mississippi farms, many taken from the estate of Alan Lomax and the Library of Congress; pornographic images from vintage magazines—Jet, Players, Sepia, Mr. Long, and Black Legs; and depictions of dancers performing the Uruguayan tango, a choreography conscripted from workers’ traditions. In these overlapping images, sometimes assembled in figurative constructions, a schema is revealed in the relations between labor and performance, performance and sexualization, sexualization and labor.

Plants constitute a life-force subjected to classification and forced migration, remarkable for their persistence and adaptability. The plant is sentient yet silent, subjected to changing environmental demands as it is displaced and commodified. Plants suggest both the ravages of colonialism and a future for life beyond humanity.

Among Williams’s plants is the artist’s new video, Annexation Tango (2020), produced in Virginia and Los Angeles by means of on-site and green-screen photography, as well as found footage. The fields that appear as backgrounds were formerly those of the Lorton Reformatory and the Virginia State Prison Farm, two facilities where incarcerated people were made to work as a condition of their sentences.

The Lorton Reformatory, first known as the Occoquan Workhouse, was operational from 1910 until 2001. It was originally established as a short-term prison for “mundane disorderlies.” Many men and women arrested in D.C.’s bars, brothels, and music halls found their way to Lorton, where agricultural and industrial labor were the primary means of “reform” and “rehabilitation.” In the ’70s and ’80s Lorton held several genre-bending musicians such as “the Godfather of Go-Go” Chuck Brown and Bad Brains frontman H.R. (aka Human Rights, née Paul D. Hudson), who is said to have recorded the 1986 song “Sacred Love” through the telephone while incarcerated. Lorton, however, is most famous for the imprisonment and torture of the “Silent Sentinels,” a group of suffragists arrested for protesting at the White House in 1917.

The Virginia State Prison Farm operated from 1896 to 2011 in Goochland, Virginia, roughly 30 miles from where the ICA now stands. The area is still used as a site for prison labor by the Virginia Department of Corrections. Inactive parts of “State Farm,” as it is known to some, are now utilized by the film industry for other forms of labor. Productions like Harriet (2019) and Lincoln (2012) have leased the lands as the backdrop for historical reenactments, staging a performance of slavery where prisoners once toiled. In Williams’s aerial footage, several prison facilities appear among plantation-style homes, open fields, and pastures, providing an uncanny convergence of past and present architectures of oppression. Superimposed onto this landscape is dancer Roderick George, performing a tango for one.

The tango is widely understood as having originated in Argentina, but the dance and the music were introduced to the Río de la Plata region by Africans, having arrived in the Americas via the transatlantic slave trade. Tango’s earliest form was the candombe, performed by African peoples in large outdoor spaces in Argentina’s and Uruguay’s impoverished areas. Argentine men took elements of the candombe to the brothels and dance halls of Buenos Aires, introducing the cheek-to-cheek proximity between dancers so recognizable in the modern tango. In the evolution of movements from the candombe to the tango we know today, we can see a gradual annexation and subsequent erasure of African influence. The only constant in the designation “tango” has been the negotiations around land, culture, and the body it implies.

Utilizing video, sculpture, and installation, A Field considers horticultural environments to explore the ways in which people, much like the crops they cultivate, can be subject to exploitation and control. By examining systems that seek to classify and manage, Williams reminds us of the potential in evasion; that there is power in remaining wild. To evade cultivation is to commit to growth on our own terms; to nurture and be rooted in our desire for change and adaptation.

ABOUT KANDIS WILLIAMS

Kandis Williams (b.1985, Baltimore, MD), an artist, educator, writer, and publisher based in Los Angeles, California. Williams’ work utilizes collage, printmaking, video, and performance to deconstruct critical theory around race, nationalism, authority, and eroticism. Williams currently lives and works in Los Angeles, California and teaches at California Institute for the Arts.

Kandis Williams: A Field is curated by ICA Associate Curator Amber Esseiva and is the third iteration of Provocations, an annual commission series that takes its name from architect Steven Holl’s design intention for the ICA’s True Farr Luck Gallery.

Production support for A Field provided in part by Night Gallery, Los Angeles.

Credits for Annexation Tango

Kandis Williams | Direction

Brian Echon | Camera & Editing

Patrick Belaga | Sound Score

Olin Caprison/VIOLENCE | Sound Score

Roderick George | Performer

Kevin Lamar Jones | Dramaturgy

Leah Adler | Movement Assistant

Nick Nauhman | Production Assistant

Tyler Lyman | Production Assistant

Departure Point Films | Richmond film Crew

Amber Esseiva | ICA Liaison

PRESS

Kandis Williams Unearths the History of U.S. Extractive Labour

Frieze

Jul 9, 2020

At the Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University, the artist presents a site-responsive project that looks at the fraught history of post-slavery labour practices across the Virginia countryside.

Can Ebony L. Haynes’s New David Zwirner Offshoot Actually Make the Art World Slow Down? She’s Banking on It

Artnet

Jul 9, 2020

The highly anticipated downtown New York space will debut in October with a solo show of work by artist Kandis Williams.

Collage and (In)Visible Histories: Kandis Williams at ICA VCU

Burnaway

Jul 9, 2020

In her newly commissioned, site-responsive installation A Field at the Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University (ICA VCU), Williams explores the entrenched narrative of agricultural labor, horticulture, and Blackness.

Meet Artist Kandis Williams, Whose Poetic Work Has a Sharp, Cerebral, and Radically Political Edge

Artnet

Jul 9, 2020

At the center of Kandis Williams’s first solo institutional show, “A Field,” on view at Virginia Commonwealth University’s Institute for Contemporary Art through August 1, a full-sized greenhouse is shrouded in sculptures of exotic plants. Inside, the artist’s 2020 video, Annexation Tango, depicts a dancer’s body floating over aerial shots of Virginia farms and California forest fires. Superimposing a dance born in the spiritual traditions of enslaved Africans over two sites that have been respectively tilled and extinguished by incarcerated people, the seemingly disparate footage illustrates a recurring theme in Williams’s recent bodies of work: the enduring link between the cultivation of plant life in the New World and forced labor.

10 AM-5 PM

10 AM-5 PM

Area Map

Area Map  Parking

Parking